What is it about?

Traditionally, the anatomical framework of the jaw has been thought to be highly conserved among vertebrates. However, we have shown that the unique faces of mammals evolved with drastically modified jaw patterns common to all tetrapods. We approached this issue from both developmental biology using mice, echidnas, chickens, lizards, and frogs, and paleontology using fossil record such as Dimetrodon and gorgonopsids. As the result, we found that the developmental primordium, which forms the jaw tip in non-mammalian tetrapods, contributes little to the upper jaw in therian mammals, but rather forms the motile nose. The mammalian upper jaw, including its jaw tip bone (so-called premaxilla), is newly established in the mammalian lineage. We propose that this previously unrecognized rearrangement has enabled important innovations in mammalian evolution, such as highly sensitive tactile and olfactory functions.

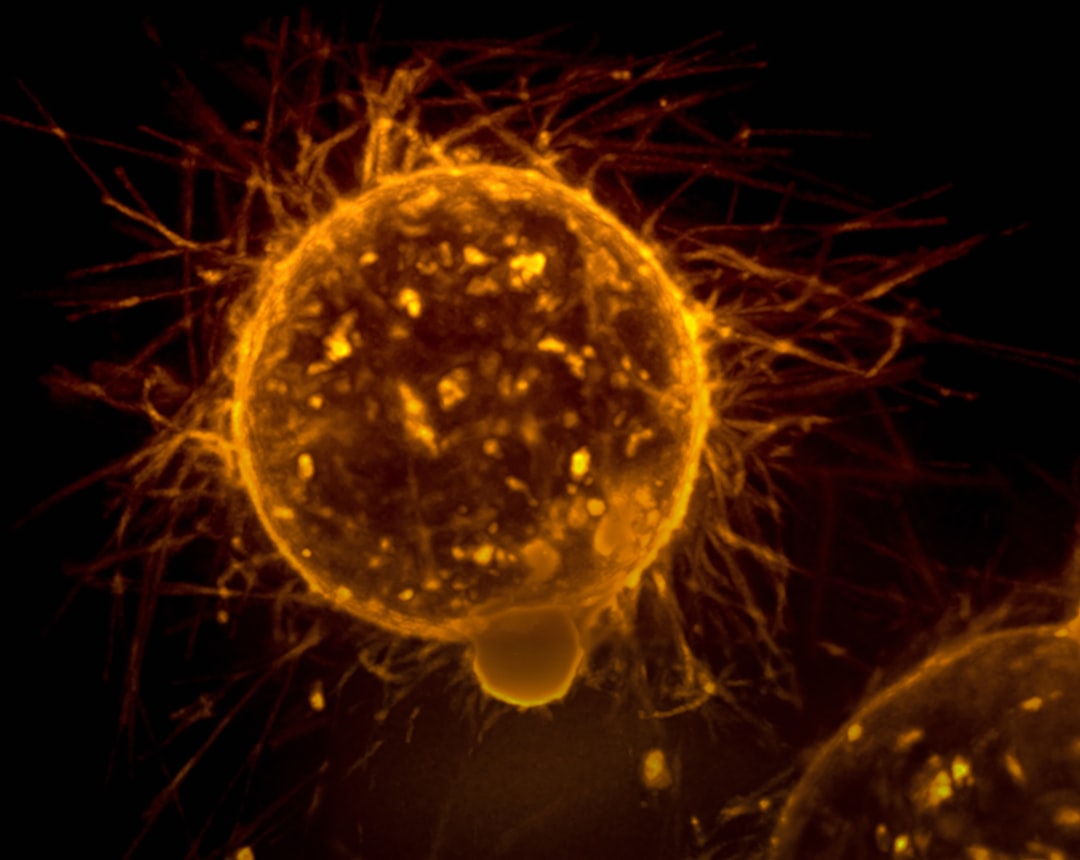

Featured Image

Photo by Christine Sandu on Unsplash

Why is it important?

This study contributes to the understanding of the evolutionary origins of the unique morphology of mammals and their well-developed olfactory functions. The study also provides a new anatomical framework for morphological comparisons between the faces of mammals and non-mammals (e.g., reptiles and amphibians), replacing a theory that has been believed for more than 200 years. This could lead to new animal models, such as chickens and frogs, for studying facial developmental disorders such as cleft lip and palate.

Read the Original

This page is a summary of: Mammalian face as an evolutionary novelty, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, October 2021, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2111876118.

You can read the full text:

Resources

Mammals’ noses come from reptiles’ jaws: Evolutionary development of facial bones studied in embryos and fossils

Official press release from the University of Tokyo

哺乳類の顔を作ったダイナミックな進化過程 ~ 哺乳類の鼻は祖先の口先だった ~

Official press release from the University of Tokyo (in Japanese)

Wie bekamen wir den richtigen Riecher? Die Nasen von Säugetieren sind eine Neuheit der Evolution – und wahrscheinlich auch für ihre Gehirnentwicklung verantwortlich

Pressemitteilungen | Universität Tübingen

How Did We End Up With The Proper Sniffer? The mammalian noses are an evolutionary novelty – and are probably also responsible for the development of the brain

Press Releases | University of Tübingen

Contributors

The following have contributed to this page