What is it about?

The Currency Act of 1763 and Sugar Act of 1764 were arguably regulatory measures, but stamp duties appealed to George Grenville precisely because he saw them as “inland duties” meant to create an unequivocal precedent for Parliamentary authority and taxation within the American colonies. Grenville and his lieutenants held their cards close to the chest during their campaign to pass the Stamp Act, and did not openly disclose their aim of creating this “great and necessary” precedent until they were pressed to defend against its repeal. Upon learning that he was contemplating stamp duties in the spring of 1764, Americans reacted immediately: They feared that the slightest acquiescence would inevitably bring tyranny and slavery: “If the British Parliament have a Right to impose a Stamp Tax,” the Reverend Stephen Johnson of Connecticut snarled in a widely reprinted essay, “they have a Right to lay on us a Poll Tax, a Land Tax, a Malt Tax, a Cider Tax, a Window Tax, a Smoke Tax, and why not tax us for the light of the Sun, the Air we breathe, and the Ground we are buried in?”

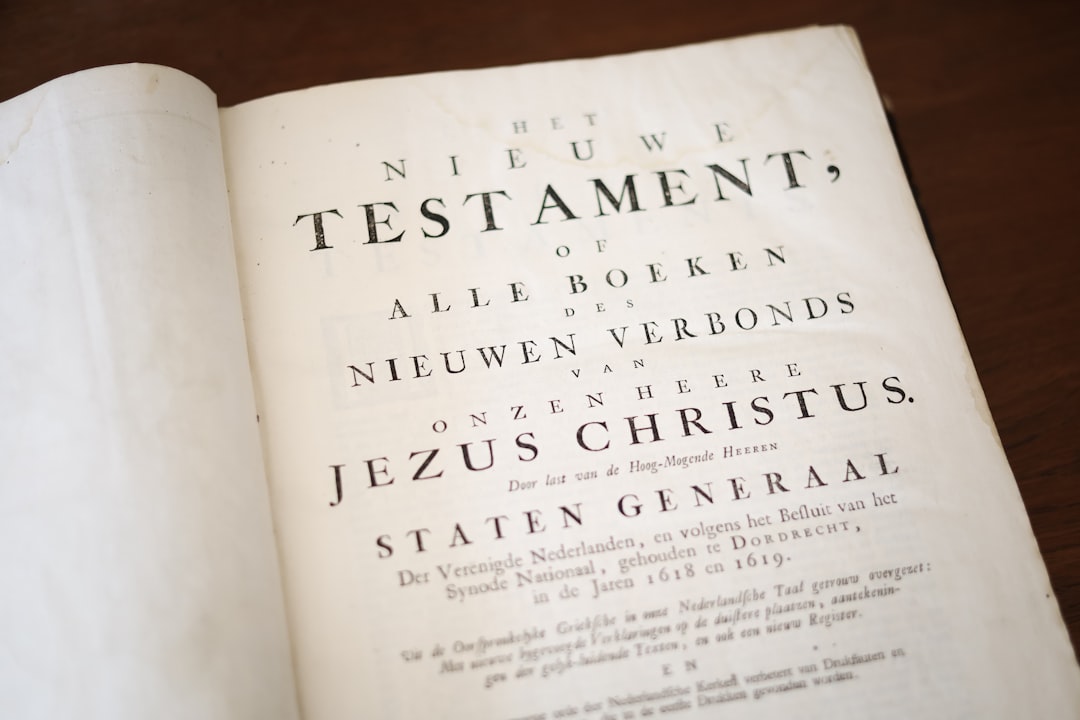

Featured Image

Photo by Tatiana Rodriguez on Unsplash

Why is it important?

Many historians agree with Bernard Bailyn that “fear of a comprehensive conspiracy against liberty throughout the English-speaking world . . . lay at the heart of the Revolutionary movement.” Many historians also agree with Jack P. Greene that the American Revolution “derived out of a disagreement over the nature of the constitution of the British Empire.” I want to suggest that an Anglo-American common-law obsession with dangerous precedents prepared the fertile soil in which both these ideological and constitutional roots of the American Revolution flourished – provided the ur-credo, if you will, that (in Bailyn’s words) triggered “immediate springs of action.” The terrifying prospect of fatal precedent (exacerbated by the grim logic of slippery slopes) gave Americans at all levels of society reasons to act against the belligerent exercise of imperial authority – whether by press gangs, army recruiters and forage-masters, or stamp officers – as an existential threat that transformed ideological and constitutional “platitudes into revolutionary imperatives.”

Perspectives

This article began when I was trying to make sense of three conflicting explanations for Grenville's decision to announce the prospect of stamp duties in March 1764 put postpone their enactment until March 1765. Although my original aim was simply to figure out how to account for his actions for my book in progress -- Rehearsal for Revolution: The Stamp Act Rebellion, 1764-1766 -- the inquiry led me to a fresh understanding of Grenville's unspoken goal, and its profound implications for my understanding of the origins of the Revolution.

Jon Kukla

Read the Original

This page is a summary of: Grenville's Postponement of the Stamp Act Reconsidered*, Parliamentary History, October 2022, Wiley,

DOI: 10.1111/1750-0206.12660.

You can read the full text:

Contributors

The following have contributed to this page