What is it about?

In the context of bilateral bargaining, a third party may promote bilateral agreement by making either binding recommendations, in which case the third party is an arbitrator, or non-binding recommendations, in which case the third party is a mediator. This paper uses game theory to explain how arbitration and mediation can affect both the outcome and process of bilateral negotiations. The theory presented in the paper has a range of applications from determining the role of governments in industrial disputes to explaining the role of intermediators in foreign policy conflicts (e.g. the role of US in Israeli-Palestine negotiations). An important insight of the paper is that the mere presence of an arbitrator can affect the outcome of the agreement even when arbitration is not used by either party. Consider an ultimatum game of perfect information where B makes a proposal to A. If B’s proposal is less than the net gain A gets if A calls in the arbitrator, A can (credibly) threaten to call in the arbitrator. The actual proposal that B makes to A will be affected by the fact that A has the outside option of calling in the arbitrator. The option of using arbitration guarantees that A gets from the agreement what he could have received if he called in the arbitrator. In fact, the option of arbitration influences the outcome of negotiations even when each negotiating party has the right to veto arbitration, since the party who gains from arbitration can commit to call in the arbitrator if the other party’s proposal is unsatisfactory. Counterintuitively, the presence of a mediator can produce adverse effects and inefficiencies in negotiations. In the case of mediation, parties do not have to commit to accept the settlement proposed by the mediator. There are two types of mediators: passive and active. Passive mediators facilitate negotiations from a neutral standpoint, whilst active mediators have a stake in negotiations. Active mediators have an incentive to contribute their own resources to help the two parties reach an agreement. However, posing as a ‘generous’ mediator can actually lead to delays and inefficiencies that would otherwise not exist. In the case of public sector bargaining, two of the stakeholders can form a coalition against the third, resulting in asymmetry in the negotiations. So far the paper has assumed that all players are aware of the others’ preferences and types, and act based on these. Relaxing that assumption, parties have access to imperfect and incomplete information. In the case of two interconnected negotiations where one party is involved in both, this party can use the information from the two separate negotiations to its advantage. This is a case of imperfect information. In the case of incomplete information, neither party knows what the other is willing and able to concede. When this type of situation occurs

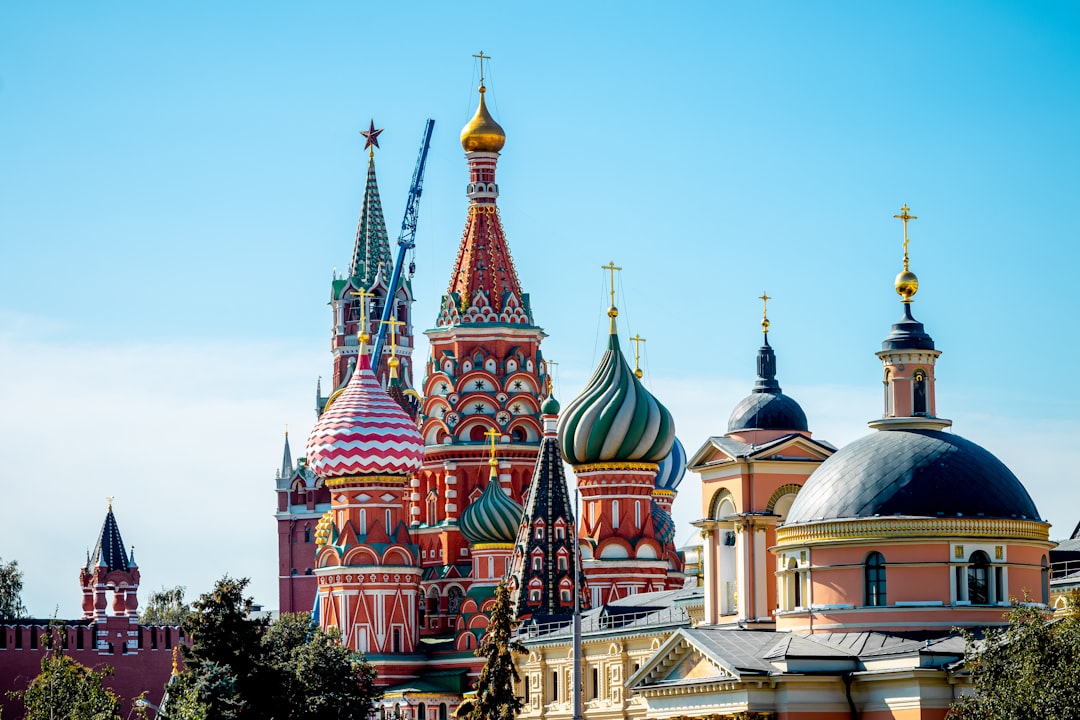

Featured Image

Read the Original

This page is a summary of: Arbitration and Mediation: an Economic Perspective, European Business Organization Law Review, September 2002, Springer Science + Business Media,

DOI: 10.1017/s1566752900001087.

You can read the full text:

Contributors

The following have contributed to this page